Writing about Covid-19 in the midst of the pandemic presents a few unusual challenges. The first is the enormous pressure to write something unique about a nearly universal experience. No background information needs to be provided, no context. We’re all obsessively reading articles online, tracking the spread and trying to protect ourselves. We’re all experts, or we feel like experts, and it’s hard to say anything that hasn’t been said before.

But my situation was unique for a few reasons. I was near about 113 km away from home in the Mymensingh, living in Dhaka, when Covid-19 first started disrupting daily life across the world. Plus, I was studying also working in the NGO, interning for the Child right’s and writing article about that, and thus reading article after article about the Covid-19 virus spreading across the globe. Yet even one day working in my desk at Banani, I harbored a deep (although private) skepticism for the way in which the media was reporting on the disease. I saw it as sensationalist and overblown, and I know that many people outside of the industry saw it the same way. It’s ironic, then, that we are now all leaning so heavily on the news to give us more information about the pandemic.

Despite effectively watching the virus approach Dhaka, we all still seemed to be blindsided by the effect it had on the city. I started reading and working from home, and my university and the office closed officially in the next couple of days. I had an easy enough job to perform from home, and for a few days I was spending my time in emptier and emptier coffee shops. Then the coffee shops closed, and then some of restaurants I used to hang out with friends and colleagues. A few days later the quarantine was announced.

Many international students from my university took that opportunity to flee home, and indeed I received an order from my university to return to my home. But I didn’t go. It wasn’t an easy decision, and I was agonizing over the right thing to do one day as I sat in the park with my roommates, soaking up the final rays of sun that we would see for a while. Both options felt wrong, but my roommates were telling me to stay. One of them looked me dead in the eye and said, “This might be your only opportunity to do something good with your life.” The severity of his tone was a joke – he wanted some company in our quickly emptying apartment – but the sentiment wasn’t. We all knew that fleeing home was irresponsible, that we’d run the risk of bringing the virus with us. And yet the next day his bags were packed, and he was ready to leave. The decision is more complicated when it’s personal: when you have to pay rent or your family wants your back, or you might get trapped in an ever-worsening situation far away from your home.

That’s why, the day before the quarantine started, I was still on the fence. I decided to go out to dinner and two hours later my friends had convinced me to stay. I suppose it wasn’t that hard. There was a certain privilege to our situation, none of us had family that was sick or working in a hospital, and I think we all felt a bit untouchable. We approached the quarantine with a sort of levity that didn’t really match the severity of the situation, but what good would panicking do? There was nothing to do except make the best of it. We had friends move into the abandoned rooms in our apartment, played Ludo and locked ourselves in.

TO BE CONTINUED…

Foysal Hasan Tanvir, United Nations Children Advisor at CHRD

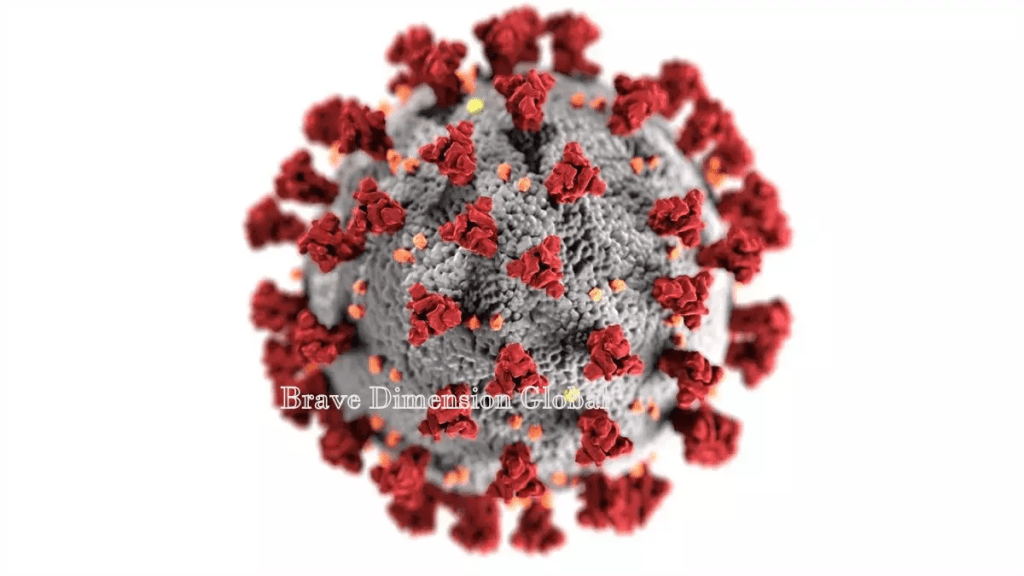

Picture: WHO

November 21, 2020